What Goes Wrong With Agile and How to Fix It

At its best, agile development methodology allows teams to produce quality work at an astounding pace. As the latest standard for working as a team across disciplines, many digital projects are committed to agile from the beginning. The intentions are good, though things have a tendency to fall off course, especially as teams are expected to constantly deliver work.

Still, we understand the issues that arise when agile breaks down: work changing mid flight, tickets getting stalled during development, and testing and QA dragging on. But through experience, we’ve also learned how to prevent it. The flexibility necessary for agile methodologies—where processes are adapted to fit team members, clients, and the nature of the work—doesn’t mean that we should simply abandon best practices.

Though many things can arise and disrupt workflow, some are more common than others, and finding solutions to these dysfunctions can largely improve the process as a whole. Identifying what is going wrong and why is the first step in shifting a team back to the right footing. The following practices and guidelines pinpoint solutions and position team members to consistently deliver high-quality work.

Problem: Lack of ticket clarity and completeness.

If there is one root cause that most commonly creates dysfunction on agile teams it is a lack of clearly documented user stories. The agile concept of The Definition of Ready seeks to make it easier to prevent this issue from having cascading effects. When work isn’t well-defined, the following consequences are quick to follow:

- Estimates are often incorrect

- Sprint commitments can be unrealistic

- Developers work slower since they need to pause to seek out answers

- Work will be executed improperly against business requirements

- Testing the work can become a nightmare

- Stakeholders can’t understand the value of a given story

Solution: Write with specificity.

When team members write out a story, every single word in the ticket is important. Everyone on the team should then be able to read the story and understand the purpose and value of the work. When the intent of a ticket is lost by a team member as they do their part, it will become painful for the entire team. Ticket clarity is also extremely important for distributed teams where members may be working on different schedules. Writing more effective tickets means:

- Describing the desired functionality or bug as if the person reading it has never interacted with the software before.

- Including URLs when referring to specific parts of a web application.

- Developers should bring up any edge cases that a story may not address.

- QA team members should speak up if they feel a ticket doesn’t give them a clear expectation of what they must be testing.

- Including images with annotations or video if a story or bug is difficult to explain.

- Scheduling additional time for backlog grooming if improving user stories together feels rushed.

- Team members from each discipline should huddle to discuss a ticket to make sure they clearly understand the work and are comfortable with it before work begins.

Problem: Hidden complexities during development.

Team members will often look at a task and create a quick solution in their mind. This skill is crucial when an emergency arises, but this quick solutioning comes at a price. Beginning work on a task without properly thinking through all of the implications can create dysfunction across an entire team and project.

Solution: Prepare with plenty of spikes.

If a team finds themselves completely unable to estimate a piece of work, there is often a need for more research. Spikes give a team a moment to pause and spend time setting the stage so that later stories can be executed properly. Just like stories, spikes should also be high quality: missing information is identified and steps to clarify ambiguity are outlined. The expected stories that will be written when the spike is finished are identified before any work begins.

- Spikes can take a while and that’s OK. Sometimes very complicated technical architecture changes need to be made before functional work can begin. Don’t be afraid to take all of the time you need, and don’t treat spikes as small blockers to be quickly resolved.

- Write down everything that was learned in the spike ticket or a documentation system, and organize the crucial details when you are finished with it.

- Spikes can seek to remove ambiguity about product, UX, design, QA, and technology work.

- Stories that are written as the result of a spike should link back to the original spike so team members understand the complexities involved and the previously made decisions.

Problem: Never removing work from a sprint.

A team’s sprint commitment should be viewed as a serious deadline that everyone should do everything they can to meet. Work shouldn’t be removed just because a team won’t be able to finish it, but there are times when removing work from a sprint makes sense and will allow a team to function more effectively as a whole.

Solution: Pull work from an active sprint if it wasn’t actually ready.

A team should be constantly guarding a sprint to make sure that only properly prepared work is making its way in. Unfortunately, teams may find themselves mid-sprint with work on their plate that is not ready and can’t be completed. This is frequently caused by unknown technical complexity, improper sequencing of stories, or technical limitations that are out of a team’s control. This is a very common occurrence for newly formed agile teams and appears more frequently if the team lacks control over underlying technical architecture dependencies.

If a ticket can’t be completed by a team during a sprint due to such complications, it is acceptable to pull it out of the sprint. This will allow team members to refocus their efforts on the remaining work rather than be dragged down by work that wasn’t properly prepared. If product or technology decisions weren’t properly thought through, continuing with work can cause more harm than good.

Pulling work out of a sprint like this is reflective of improper planning by a team. A piece of work should not be pulled out of a sprint if it was actually ready and the team just failed to complete it. Any tickets pulled out of a sprint should be tracked and any points assigned to them should be deducted from a team’s velocity. A large portion of a retrospective meeting should be dedicated to what went wrong in this regard and how it can be prevented going forward.

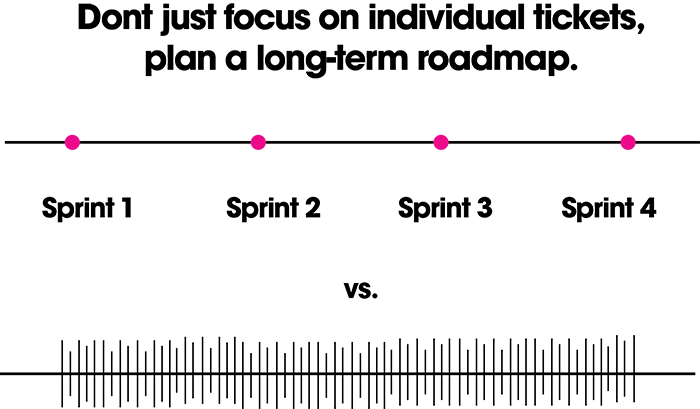

Problem: Planning only at the task level.

Teams work best when they are given clear, well-defined, executable tasks. Agile processes split work up into small pieces, making large projects possible, but this can often be at the expense of failing to plan at a higher level. A list of tasks often lacks the nuance that is necessary to visualize the dependencies between complex technical tasks and upcoming product features.

Solution: Plan at a higher level.

For planning sequenced stories and technical tasks, a product road map with a rough timeline, and identifying what features will be delivered in which sprints, will make sprint planning and backlog grooming much easier. A product roadmap with approximate sprint alignment also has the added bonus of conveying to stakeholders a rough timeline of when they’ll receive features they’re interested in. This can also be used to make an organization or client who’s used to waterfall style software development more comfortable with what they can expect from an agile team.

Figuring out technical details and architectural approaches in spikes is absolutely necessary, but keeping that knowledge in separate tickets can create a situation where the overall technical architecture isn’t comprehensively explained in one place. A wiki such as Confluence is a great solution to this problem. A wiki page with formatting lets a software engineer tell a story that relates the product, design, and UX pieces to the technical solution and explains how they all interact. This also makes it easy for others to review a proposed architecture and has the added bonus of acting as documentation for new team members to get up to speed quickly.

Problem: Starting work before it’s truly ready.

All too often, teams will look at a story or bug and in their eagerness to start the work will only think about blockers for development. Agile methodologies work best when work can smoothly progress from idea to acceptance, and it is very easy to be short-sighted when it comes to the activities required for tickets to be properly tested.

Solution: Being ready all the way through QA.

Usually, stories are thought of as ready when all of the details and pieces are there for development to begin, but this is only half of the equation. It is all too easy to overlook any blockers that will arise during testing until a team runs right into them. Before claiming that a story is ready, ask yourself a few questions:

- Is a test plan defined for a story and is the team confident they can complete testing without running into any major issues?

- Are there test cases that we’ll need to prepare by modifying our data or triggering specific external API responses?

- Do we have the physical devices such as tablets or phones to test this properly?

- Do we need the help of a different team, such as operations, to setup and execute a test?

These questions should be asked during backlog grooming and sprint planning. This works best if there are multiple QA team members so one team member can be sorting out these types of issues early while a second is handling the actual testing. QA team members should flag ambiguities and issues that could add complexity to the testing process early and work with the rest of the team to find solutions before stories are considered ready.

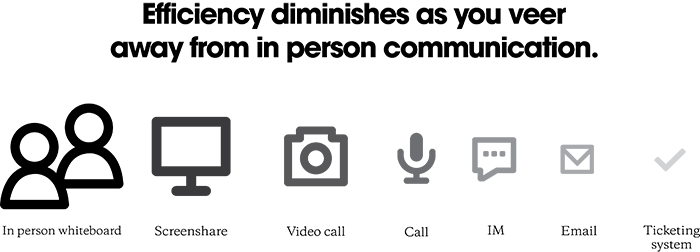

Problem: Overreliance on ticketing systems for communication.

Agile teams often live or die by their ticketing systems, and this is especially true for distributed teams. It’s great to have feature-related discussions on a public location, such as comments on a ticket so other team members can be aware of decisions that are being made. It’s also helpful for QA to reference these conversations when testing a ticket. There are times, though, when discussing issues in this manner is grossly ineffective when compared to higher-bandwidth forms of communication. Behavior such as repeatedly assigning a ticket back and forth between team members can also feel like arguing or trying to blame someone for a bug.

Solution: Not relying solely on communication in tickets.

Tickets should always be the source of truth and this is especially necessary for a distributed team, however they should not be used as the primary form of communication on a team. Assigning a problem ticket to a team member without an explanation can also feel like blaming them rather than working together to find a solution. Comments on a ticket can also be easily misinterpreted since they lack any tone or emotion.

If you ever spot this kind of behavior on a ticket, encourage the team members involved to hop on a call together, screenshare, or better yet set aside an hour in a conference room to clearly outline the problem and hammer out a solution together.

Problem: Not accepting tickets because they aren’t exactly what we wanted.

Closing out work is the momentum that keeps an agile team moving. This validates that the work a team is doing is meaningful and gives them the fuel to keep going sprint after sprint.

When work is being accepted by stakeholders it is very often the case that folks will say, “This meets the acceptance criteria, but let’s just add one more thing” or, “It’s close, but not exactly what we want”. It is OK to say this, but unfortunately it can result in issues being left open rather than closed out. This is known as Scope Creep and can shift a team from the stable footing of hammering out work, to the unstable position of constantly changing direction while trying to satisfy suggestions that may not be well thought through.

Solution: Being strict about acceptance criteria.

During acceptance of stories, a team should be very strict about determining whether a story meets the originally defined acceptance criteria. If there is additional desired functionality, it should be spun off as a new ticket so the original story can launch and be closed out.

If stakeholders are trying to squeeze more functionality onto stories, encourage them to write new tickets themselves and attend backlog grooming sessions where they can be prioritized. This will give them a sense of being heard and assure them that the features they need are on the team’s radar and can be included in the next sprint.

The quest for perfection with every story can prevent small incremental improvements from being delivered quickly, defeating the purpose of agile.

Bottom line: Constant introspection.

These guidelines are the result of having a team that approaches software development with the attitude that they will always have a lot to learn. Team members should take detailed notes during each sprint on what worked and what didn’t go well, so they can bring the issues up in a proper sprint retrospective. Team leads should also ensure that plenty of time is set aside for retrospective meetings, and that they consist of an environment where team members can be completely honest about mistakes without expecting anyone to blame them. A properly functioning agile team will eventually identify these problems and solve them, but there’s no reason not to watch out for them starting with sprint zero.